April 8, 2020 JWT Access Tokens Refresh Tokens Express NodeJS APIs

JWT Access Tokens

Okay I learned some pretty awesome stuff about JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) and handling access tokens today.

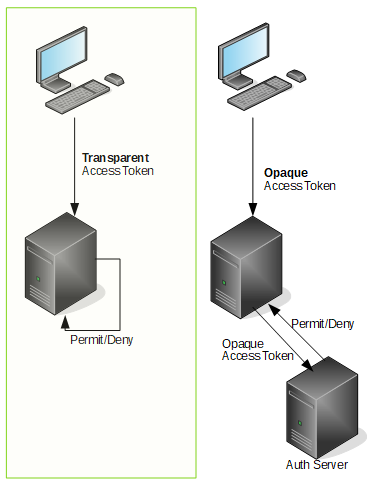

Access tokens come in one of two broad varieties: opaque and transparent. Opaque tokens are random sequences of alphanumeric characters with no embedded data - they simply act as a pointer (identifier) for some information to be looked up. Opaque access tokens are not JWTs, and are outside the scope of this post.

Transparent access tokens on the other hand, do indeed have data embedded directly in them. In fact, they might look like random strings of characters, but they’re actually base64 encoded JSON objects (tip: you may notice that all JWTs start with an “ey” … that’s because “ey” is the start of any base64 encoded string that begins with the {" character sequence (… as all JSON object do). By definition, a JWT is a transparent access token, because its contents can be decoded and read. Don’t believe me? Try throwing your JWT into this site. In this post, we’ll dig into a few more cool things about JWTs and how they are handled between client and server using a couple popular JavaScript packages (axios and jsonwebtoken).

One of the great powers of JWT formatted access tokens is that they allow servers to grant authorization to users without having to reach out to an authorization server or database each time a validation is needed - which means performance gains on both the server and the network.

Wow! Sounds too good to be true, right??? Well it is true because, as mentioned earlier, all the data needed for the authorization is embedded and readable in the token itself. On the server side, any transparent access token (JWT) received contains a signature, which is then verified (to make sure it was signed using a protected secret kept on the server - if so, we can trust that this token was generated directly on the server at some previous point).

This figure shows that a token can be validated on the resource server without needing to reach out to another server to perform a lookup.

Because JWTs are often set to expire (for security reasons, they should not remain valid forever) the verification process must also check the token expiration. The IETF specification includes a number of “regiseterd claim names” which are basically reserved JSON property names to be included in a JSON object in any JWT. One of these properties is exp which identifies the expiration time of the JWT, specified as the number of seconds since 1970-01-01T00:00:00Z.

By having this date on hand, both the client and the server are able to quickly process if the token is still valid. Versus an expires_in: 1hr field, (which I’ve seen before) which, when used alone, doesn’t give complete enough information for a stateless evaluation.

Next, I learned that the jsonwebtoken package available for install via NPM contains all the utilies needed to set and verify expiration. The following code snippet will set the tokens exp field to be set for 60 seconds from the moment it is signed.

jwt.sign({

data: 'foobar'

}, 'secret', { expiresIn: 60 });When sent back to the server, the .verify() method will evaluate that the token has a valid signature and is within the expiration limit. If either is not true, it will throw an error, so you’ll want to wrap this line in a try/catch.

let decodedToken;

try{

decodedToken = jwt.verify(jwt, secret);

}

catch(err){

//handle error condition

}The output of the .verify() function is the decoded JWT in JSON format, so in the snippet above, the decodedToken variable we set can then be used to read or do some work directly with the decoded JWT.

The .decode() is also available if we want to work with the JWT itself, but aren’t looking to validate it. These values

I’d be remiss not to mention this very handy site that offers a great UI for validating, encoding, and decoding JWTs: https://jwt.io/#debugger-io.

Refresh Tokens

Okay - now that we have JWT access tokens down, what about refresh tokens? A refresh token is a special token that allow a client application to have a new access token issued without the work of requiring a new round of login and credentials checking every time an access token expires. Where do they come from? They are generated by the server at the intial time of sign-in, and sent back to the client with the access token. Because they are longer-lived, the security for refresh tokens should be higher than that for access tokens. I.e. They should only leave the backend when being sent to the authorization server, and the backend itself should be secure. Users and admins have more ability to invalidate refresh tokens than they do Access Tokens. Some reasons that may happen are as follows:

- the Auth server has revoked the refresh token

- the user has revoked their consent for authorization

- the refresh token has expired

- the authentication policy for the resource has changed (e.g., originally the resource only used usernames and passwords, but now it requires MFA)

In practice, the authorization service typically makes an endpoint available at /auth/refresh for the client to send a refresh token and have a new access token given in return.

Tricks for effective token lifecycle management

Tokens have a lifecycle and managing them can potentially add a lot of overhead to your app. When you think about it, there’s a lot to do each time you want to make a call to your token-protected API:

- Make initial token request and keep tokens in secure storage

- Ensure your access token is not expired

- If expired, use your refresh token to obtain a new access token

- Check error responses from API to ensure they’re not due to access token expiry

That’s a lot to do. Luckily, there are some cool tricks and tools that can come in handy:

JWT Storage: Cookies vs Web Storage

Tokens are very sensitive pieces of data that must be stored somewhere.

Web developers have can leverage several different storage mechanisms provided by the browser (e.g. cookies or web storage like Local Storage and Session Storage). The contents can be viewed in the developer tools on the “Application” tab.

The Local Storage option is nice with convenient features features (unlike Session Storage, data persists beyond a single session or when the browser is closed), but is left vulnerable to XSS attacks.

When delivering a Single Page App (SPA), it is recoommended to store your application’s JWT in cookies because they can provide additional security features which don’t make it accessible to JavaScript code and only allow it to operate over an https connection. As you will see in this demo, we violate this best practice and instead use Local Storage (Web Storage), partly for convenience and because I don’t have trusted certs setup in my demo app.

Axios Interceptors to the rescue!

Now that we’ve covered storage, let discuss management of token lifecycles. Token expiration checking and refresh would be an annoying pain to implement in every single location where we want to make a call to our backend. Luckily axios has a feature called “interceptors” which intercept a request or response before it’s handled by .then() or .catch(). Usage might look like this:

axios.interceptors.request.use(function (config) {

// Do something before request is sent

return config;

}, function (error) {

// Do something with request error

return Promise.reject(error);

});We will use this feature to intercept all requests/responses to our backend API. Luckily we don’t have to apply interceptors universally throughout our app. Instead, we can create a generic axio instance to communicate with our backend and apply our interceptors to that instance, then import it wherever we need to make calls to our backend. and not just our allow us to centralize this logic and apply it to all outbound/inbound requests/responses.

let token = myStorage.accessToken // get token from storage

//Option 1: Set a token in the base instance

const instance = axios.create({

baseURL: "http://localhost:3001",

timeout: 10000,

headers: { Authorization: `Bearer ${token}` } // <-- Here we set the token in the header

});

//Option 2: Set a token using an interceptor

instance.interceptors.request.use(config => {

console.log("REQUEST SENT");

config.headers.Authorization = `Bearer ${token}`; // <-- Here we set the token in the header

config.headers['Content-Type'] = 'application/json';

return config

})This is great. Using either of the options above, we can be sure that we have our access token being sent to the server with each request.

Now, what about refreshing the token when it expires? In theory, we could could create some logic that checks for expiration client-side, but we’ll choose not to do that since it’d rely on system clocks being synced. The alternative we’ll choose is to send the original request as-is, but listen for any error responses that suggest and expired token. If we find one, then we’ll use an axios response intercepter to make two more calls: one to refresh the access token, and another to replay the first call using the new acess token.

//setup error interceptor on our instance

restApi.interceptors.response.use((response) => {

return response //Let normal responses pass through

}, (error) => {

if (error.response.status === 401 || error.response.status === 403) {

let instance = axios.create({

baseURL: "http://localhost:3600",

headers: { Authorization: "Bearer "+localStorage.getItem("jwt-access-token") }

});

console.log("Token expiry error intercepted. Sending request for new access token.")

//Let's try to use our refresh token to get a new access token.

return instance.post('/auth/refresh',

{"refresh_token": localStorage.getItem("jwt-refresh-token")})

.then(resp => {

if (resp && resp.status === 201) {

console.log("Success! Obtained new access token. Now repeating original request.")

// put new tokens in LocalStorage

localStorage.setItem("jwt-refresh-token",resp.data.refreshToken);

localStorage.setItem("jwt-access-token",resp.data.accessToken);

// 2) Change Authorization header

axios.defaults.headers.common['Authorization'] = 'Bearer ' + localStorage.getItem("jwt-access-token");

// 3) return originalRequest object with Axios.

return restApi.get("/users").then(resp=>{

return resp

});

}

}).catch(err=>{

//Error, redirect to login

console.log("Error requesting new access token. Redirecting to /login.")

window.location.href = "/login";

})

}

else{

//redirect to login

window.location.href = "/login";

}

})Does it work? I hope! I have put this all together into a proof of concept application (React/Mongo/Express/Node) that you can find on my GitHub.

References

- JSON Web Token (JWT) IETF standard

- JWT.io debugger

- jsonwebtoken NPM documentation

- Handling access and refresh tokens using Axios intercepter

- Axios error handling